- Home

- Palmer, Jacob

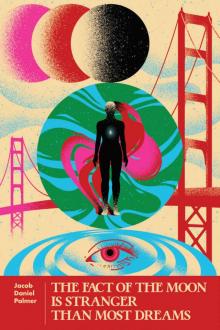

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams Page 2

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams Read online

Page 2

“Dying capitalism,” Kenner said. “It’s a dying religion, but now everybody is turning to VR to give their life meaning. Do you and Abram still have that janky old VR setup?”

“Nah, we got a new one a few months ago. I got it with an artist grant. I used it for a few online teaching gigs. Abram and I try not to get on it that much, though. You know how he is about that stuff.”

“Oh yeah, he used to say it made him feel apocalyptic,” Kenner said, laughing. “When he and I were roommates in that house on Page Street, I actually bought one of the very first high-end VRs before they were cheap. I was making bank at this sweet-ass chef gig in North Beach. We would get so fucking ripped and then be on the VR all night. I think we both got burned out way back then. We were the first VR burnouts.”

“Yeah, but that was before they had any good games for it, though. Way before they had any life-optimization programs or therapy bots or anything psychedelic.”

“You know, Abram told me once,” Kenner said, shifting and uncomfortable on his small perch, “that what got to him about VR was that it’s a simulation of reality, and a simulation always hides some-thing. But when you think about it, it doesn’t hide the truth—it hides the fact that there is no truth, that it’s all nothingness behind the simulation. When he put it that way, he turned me off VR, too. That’s when we started making music together instead. Recorded that album.”

“Yeah, yeah, he’s told me that same thing. I think you guys were just really stoned when he came up with that. Abram always turns into mister wise-old-man philosopher.”

“That’s true, that’s true,” Kenner said. “It’s the same with capitalism. Like you were saying before, the rich rule from behind symbols. They create a simulation, create a virtual reality, myths and stories, to justify their place at the top of the pyramid. We have to reject that, though, create our own reality. Create a reality where I’m not eating the equivalent of an entire plastic garbage bin every five years. The rain washes trillions of microplastic particles from car tires into San Francisco Bay every year. Plastic is swimming in the bay, swimming in our blood, swimming in our brains.”

“Sure, except I can’t remember the last time it rained, and before you go off preaching to people to create their own realities, keep in mind that people are burned out and tired and it’s a lot easier for them to live their lives inside a simulation than to examine their situation. Reality shit. Peo-ple deserve a break. Wait a minute, I forget. Are we talking about capitalism or virtual reality? You want some wine? Abram bought a bottle to celebrate his artist-in-residence thing, and we haven’t finished it. It’s pretty good, and I don’t usually like red wine.”

“Oh, shit. Alright, alright,” Kenner said, laughing and coughing. “I’ll take a small glass to cele-brate. Abram and I used to drink so much wine back in the day. We’d get drunk as hell and go busk at Alamo Square Park. We were the only ones. Nobody else ever busked there for some reason. Seems like a lifetime ago now. Different people.”

Edie poured a vintage Smurf juice tumbler to the brim with deep red wine as Kenner began dig-ging through his dirty green backpack. A wave of marijuana fumes escaped from the open bag like a musty yawn.

“Wait, can I see the bottle? I remembered I don’t do California wine anymore post-Fukushima. Scientists found traces of Cesium-137 in a bunch of California wines they tested. That shit blew across the ocean. This is a California wine, but it’s a 2022. What year did Fukushima happen?” he said, scruti-nizing the bottle, one hand still rummaging blindly in his bag.

“I don’t know,” Edie said in monotone.

“Oh well, whatever. I guess I’ll have a glass,” Kenner said. “You know what, though? I’m just going to look it up real quick or it’ll drive me crazy.”

Kenner tapped the question into his phone, and an unintelligible barrage of digital speech blared from the busted speaker.

“What the fuck was that?” Edie said.

“I set my phone to speak at six hundred words a minute. I want to get it up to eight hundred words eventually. I know a blind dude that has his phone set up that way, and he can understand it per-fectly. Lots of blind people do it. He said the section of the brain that normally responds to light is re-mapped in blind people to process sound.”

“Yeah, well, good luck with that.”

Kenner played the response again, shrugged, and turned his phone over. Edie handed him his wine.

“I can eventually understand it if I hear it a few times,” Kenner said. “I won’t drive you crazy play-ing it over and over. Maybe I should close my eyes when I listen to it.”

“If the world was easily understandable,” Edie said, filling her ornate teacup, “art wouldn’t exist.”

“Yeah . . . and no true artist tolerates reality. Nietzsche said that, I think.”

“Sounds like Nietzsche—patron saint of intolerant men. How do you like the wine?”

“It’s great. Almost kind of smoky-tasting,” Kenner said, swirling his wine and spilling a bit of it on the table. “You hear about that fire up north?”

“Yeah, it’s horrible. Entire towns burnt up. It’s getting hard to remember a time when we didn’t have fires all summer. We ordered a new air purifier first thing when Abram got this artist residency,” Edie continued, staring into her wine, focused on the light tracing the small concentric ripples. “Seems like people barely talk about the fires much anymore. I guess it’s easier to just shut up and buy an air purifier and live your life.”

“I was up north a couple years back during those really bad wildfires around Shasta. Shit was cra-zy. It rained ash for weeks. Looked like the apocalypse,” Kenner said, a note of enthusiasm in his voice.

Your apocalyptic enthusiasm is just a way of dealing with anxiety about the approach of death, Edie thought and almost said, then changed the subject. “I think Abram should be back soon. Maybe we could all make something to eat.”

“Cool, cool. You wanna smoke first?” Kenner said, producing the pipe he had been distractedly rummaging for in his bag during the entire conversation.

“Nah, I think I’m good. I just smoked before I took a nap.”

“You sure? This is good shit. I got it on my way in. Weed is so fucking expensive here in the city, though. I started arguing with the clerk. I was like, ‘This is bullshit. I can get the same damn thing in Stockton for—”

“Okay, Jesus Christ, whatever. I’ll take a hit.”

They sat at the table in stoned, awkward silence for what seemed to both of them like minutes.

“I should really stop smoking so much. I think it’s been affecting my memory,” Edie said.

“How has it been affecting your memory?”

“What?”

“Like, how? What don’t you remember?”

“I don’t know what I don’t remember. If I remembered what I forgot, then there wouldn’t be a problem.”

“That’s true, I guess, but you have to forget to remember.”

“What do you mean?”

“You have to forget to remember. There’s only so much room in your brain. We’re forgetting all the time.”

This struck Edie as beautiful and sad and maybe stupid.

Stoned moments passed, unmoored. Edie thought to put on music but then second-guessed the idea. Kenner poured himself another glass of wine.

“You know something else I was thinking about the other day while I was at the park feeding squirrels?” Kenner said, spilling more wine with his large, shaky hands.

“You were at the park feeding squirrels?”

“Yeah.”

“What were you feeding them?”

“Nuts. But anyway, what’s most unique or . . . no, what’s most noticeable to us, like human facial features, probably isn’t noticeable at all to other species. A human face means jack shit. Animals only know what they need to know, right? Who am I to that bird in the tree? No one, no persona. My face is just a horrible thing on one end of a horrible thing, moving through the f

orest on two stumpy horrible things. Stuck to the ground. Birds must think we’re cursed creatures . . . and they’re right.” He laughed a hard, genuine laugh as if he were alone in the room and took a long hit from his dirty glass pipe, filling the kitchen with smoke. He offered it to Edie and she did the same, and then they both sat again for a long time, saying nothing. Kenner squinted and read the back of a green bottle of allergy pills on the table. He loves the sound of his own voice. The greatest evils in the world are committed by nobod-ies, no persona, no face. A human being who refuses to be a person, Edie thought, watching him.

“You want this last bit of wine? It’s Jesus’s blood,” she said.

“You know, I sold blood a couple weeks ago.”

“Your blood or somebody else’s?”

“Seriously, I was broke. I spent all my UBI getting my fucking truck fixed.”

“How much money do you get selling blood?”

“Not much. I almost would’ve rather kept my blood. You know that America is one of the only countries in the world that pays people to donate blood, and they sell most of it overseas? Blood ac-counts for eight percent of U.S. exports, more than corn.”

“How do you know all that? Did the nurse tell you?”

“Nurse? There wasn’t a human in that place except me. It’s all automated. All that information was on their website. I read about it while I was sitting there getting poked.”

“Want me to do your tarot?” Edie asked.

“Sure, I guess . . . I mean, I—”

“Listen, Kenner, mister bummer facts. Let me lay this on you: Isaac Newton was totally into tarot and astrology and all that shit. In fact, he was into it more than anything else, and he just accidentally discovered gravity.”

“Is that true?”

“Of course. He only studied math to get better at calculating star charts. Tarot works just like AI. We identify patterns in the data and extract meaning from the correlations.”

“Alright . . . I just—”

“Pick three cards.”

“Okay, do I—”

“Just pick three cards.”

“Okay.”

The Tower, the Devil, the Magician.

“Hmmm. Okay,” Edie said with a forced stoned sincerity. “A profound change is coming, some-thing that could shake your world to its foundations. You see the Magician card? He’s pointing at the sky with one hand and the ground with the other.”

“As above, so below,” Kenner said.

“Yes, the outer world is a direct manifestation of the inner world.”

“Like we were talking about before, an inner world and a human-made simulation. A world of signs and symbols, representations.”

“Have you been feeling depressed?” Edie said, touching the Devil card.

“I don’t know . . . I get pissed off more than anything else. I’ve got anger issues for sure.”

“How’s your sleep?”

“I don’t sleep.”

“Do you have nightmares?”

“I used to have horrible nightmares as a kid, almost every night. My parents wanted to take me to a therapist for it, but they never did. Then, when I was about thirteen, I found this book about lucid dreaming and was obsessed. I learned pretty much everything you can know about it.”

“Do you have lucid dreams a lot?”

“Nah, barely ever. I don’t really need them as much anymore, I guess, if that makes sense.”

“So lucid dreaming was a tool for you to take control of your dreams? A way to shape the dream world into something safe?”

“The thing is, though, the dream world is the real world. Us sitting here is the illusion. The symbols are on this side.”

“Do you actually believe that?”

“I always kinda believed it, but after all the psychedelics I’ve taken, now I totally believe it.”

“Have you ever thought that maybe all those psychedelics gave you brain damage?” Edie said.

They burst into rolling waves of stoned laughter, Edie holding her sides, Kenner red-faced and coughing.

“Oh, shit. Abram tried to call. He texted fifteen minutes ago,” Edie said, still laughing after ex-tracting her phone from under the tarot card deck.

“He’s on his way? I can drive and pick him up.”

“He said, ‘Be home in a minute. Had to stop by my bank. I’m in line. You won’t believe the day I had. Security threw me out. Was able to get my camera, though. My ring light and everything else is still there. Said they’d mail it. Everybody seemed scared. The HR lady slipped me a memory card! I’ll be home in a second.’”

“What?” Kenner yelled, bumping the bottom of the fold-out table with his knees.

“Wait, did Abram tell you about his artist-in-residence thing?” Edie said.

“He kind of told me about it last time I talked to him. It’s like a tech company that—”

“It’s a startup that makes microsatellites. They’re called Oversight, and the O is like a little Sat-urn. It’s cute. They sell satellite imagery to whoever has the dough for it. It’s pretty expensive. Abram started the residency a few weeks ago, and the stipend is pretty good. He takes photos of the data scien-tists while projecting satellite images onto them. Abram said the energy has been really weird there the whole time. Really negative and intense. Ominous.”

“Are you serious?” Kenner said, wild-eyed.

“Why are you freaking out? It sounds like the company just went out of business or something. It happens all the time. It happened to me at a residency a couple years ago. A credit-checking app startup on Montgomery Street. They were assholes about it, too. Had security escort me out when I tried to collect my stipend.”

“I don’t know . . . What’s up with that memory card? Why would someone there slip him a memory card? Abram shouldn’t have gotten mixed up in that surveillance shit in the first place. They probably have a satellite watching him walk home from the bank right now! Now he’s implicated in something. Abram didn’t tell me anything about the residency because he knew that if he did, I’d go apeshit.” Kenner stood, spilling wine on the kitchen floor and clumsily blotting it with the corner of his backpack.

“Abram was just the artist in residence. Nobody gives a shit about the artist in residence, believe me. He just sat scientists down in a chair and took their picture. The memory card was probably just Abram’s and he forgot they had it. They were probably just returning it. I remember him saying some-thing about them wanting to check the card from his camera once.” Edie was laughing but, because of the weed, growing paranoid and doubtful.

“I don’t know . . . The foolish reject what they see, but the wise reject what they think. Know what I mean? We have to see what’s on that memory card, or maybe we shouldn’t. Have to approach this whole thing carefully.” Kenner took another long hit and sat back down.

“No.”

“NASA released photos of it years ago—on accident, of course—and then claimed it was just a pic-ture of some space garbage floating around. It’s a satellite, possibly. No, actually probably of extrater-restrial origin. It’s been up there for thousands of years. Nikola Tesla picked up signals from it in the late 1800s. It’s about the size of one of our satellites, but it’s completely black, and it’s a weird scutoid shape. The military can’t get close to it because all their instruments stop working. They’re afraid to shoot at it, so they just observe what they can from a distance.”

“Hmm . . . Interesting,” Edie said, half listening while fixing herself a sloppy peanut butter sand-wich. “What does that have to do with Abram or the memory card?”

“I’m just saying there’s a lot of crazy shit going on in orbit, and there has been for a long time, and I’m surprised a private startup satellite company was even allowed to poke around up there. It’s one big surveillance network. As soon as you leave this apartment, you’re on camera. Walk to the bank, use the ATM, use the crosswalk, get on the subway, they’re watching you the whole time. Plus, they’r

e watching you from space. And drones! They got every angle covered. They track your movements street by street with your phone. Hell, they’re counting your steps, breaths, and heartbeats. You come back home, and they’re monitoring your electricity usage. They know when you turn on the bathroom light at 3:00 a.m. to take a piss.”

“Yeah, sure, but what’s the point in worrying about it? You can’t do anything about it and still live in the city. I’m not an off-the-grid hippie.”

“You can do stuff, though. Over-disclosure. Lawyers do it. Send a shit ton of junk documents and legal jargon to bury a pertinent detail in the middle of it all. Overload the system, hide inside the noise.”

“Like wearing shirts and masks and stuff with patterns that mess up recognition systems? I’ve been doing that for years.”

“Yeah, I guess like that. But you should also especially be careful of where, and how, you use your phone. There are barely any police around anymore, but now we have surveillance up the ass. I predict-ed all this shit. Now they run on the philosophy that all this recorded data means that everyone is likely to be guilty of something in the normal course of their day. If they want you, they’ll just swoop in and get you for anything.”

“Whatever, it’s always been like that, at least for us brown folks. Welcome to the club. You want half of this sandwich?”

“I’m not doing bread right now,” Kenner said, looking disdainfully at the sandwich. “All I’m saying is, you should constantly be aware. Once you see the boundaries of your environment, they’re no longer the boundaries of your environment. Draw a bigger circle.”

“Yeah, sure. Maybe,” Edie said, smacking her lips. “What were we originally talking about, though? Aliens?”

After a fumbling sound of keys in the hallway, Abram entered, smiling.

“What are you two doing in here? I could hear you talking from the street.”

“We were just trying to figure out where you were. I was about to come looking for you,” Kenner said, lifting Abram from the ground with a bear hug.

“It smells like weed in here.”

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams