- Home

- Palmer, Jacob

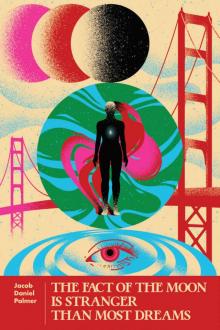

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams Page 3

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams Read online

Page 3

“We smoked a little,” Edie said, laughing.

“Did you two bastards drink my wine?”

“We were drinking because we were worried about you,” Edie said, playfully hiding the empty bottle behind her back.

“What a fucking day,” Abram said, taking the memory card and phone out of his pocket and laying them on the table, atop Kenner’s tarot spread.

“Oh God,” Kenner said, picking up the memory card and examining it.

Abram’s phone lit up with an email notification. He read silently and then laughed. “You aren’t going to believe this. I think I just won a ten-thousand-dollar artist’s grant.” He read the message again.

Edie screamed and kissed him, jumping up and down.

“Yeah, man! That’s what I’m talking about! Let’s go to the casino,” Kenner said, clapping loudly.

“Get the fuck out of here,” Edie said, shoving Kenner and rolling her eyes.

“The thing is, though,” Abram said, “I never finished applying for it. I filled out half of the entry online a month ago but never submitted it. It must be a mistake.”

“What does the email say?”

“It says congratulations, fill out these e-forms, and they’ll send follow-up info.”

“You sure it isn’t a scam?” Edie said.

“I don’t think so. It seems legit.”

“Well, fill out the fucking forms!” Kenner said, laughing and patting Abram on the back.

“How much is ten thousand dollars, though, really?” Abram said, reading the email again. “Maybe I should just sit on it for a while.”

“Well, if you got ten grand every day,” Kenner said, “from the day Columbus first set his rapist foot in America, all the way until today, you’d just hit a billion dollars right now. Ten grand is chump change.”

“What are you talking about, Kenner? How would you even know that?” Edie said. “Did you know there are more trees on Earth than there are stars in the Milky Way?”

“Jesus Christ, you two are fucking stoned,” Abram said. “I think I know what I want to do with the money, though. I just had a vision of burying it in the desert.”

“Umm, yeah, don’t do that,” Edie said.

***

Out of the shower, Abram found Edie in bed, asleep, the laptop open and playing Alice in Wonderland, her face illuminated, cartoon music blaring.

“Iloveyoubabygnight,” she mumbled, as Abram reached over her to close the computer.

She drifted immediately back into her stoned, heavy sleep. Everyone was stoned now and nearly all the time, Abram thought. Why not? It doesn’t matter.

Abram had stopped smoking after developing a persistent stoner’s cough that morphed into the blinding white pain of pleurisy. After a year and three pointless emergency room visits, the ailment van-ished as quickly as it had come. Abram had of course tried edibles instead but didn’t like them and felt they made him even more prone to procrastination than usual, so he went cold turkey and made himself a part of a pitiful sober minority.

Abram thought again about the artist’s grant, thought of his bank account. He thought of the old days, before Edie but still in the same small rent-controlled apartment. Thought of the times before, of the protests that turned to riots and looting, how he was nearly shot in that vague other life. In despera-tion, the government gave the people universal healthcare (barely adequate), the police were defunded (and replaced with ubiquitous surveillance), and universal basic income rolled out (just barely enough to survive).

Though the riots ceased, viruses continued to run rampant, both natural and lab-made. But in spite of the sick and dying, it still felt like a revolution, a victory. It was a techno-utopia. It was a flour-ishing that quickly turned into a torpor and then into nothing at all. The wealthy few were wealthier than ever before, and sequestered like never before, and everyone else just got by, threw themselves into innocuous escapist pursuits.

New drugs, mostly opiate derivatives, came out constantly and were cheap and freely available. Psychedelics flowed in and out of fashion. If you were a spiritually centered, healthy person, you only smoked weed and dabbled in everything else. Total sobriety was suspect.

Climate change was on an inexorable, tragic trajectory, breeding hurricanes and crop failures. Cal-ifornia burned half the year and it was too late to do anything about it. The cause was lost.

People were desperate to escape. Home VR/AR gaming systems were soon deemed a basic hu-man right, and so that was where people went, where they played and fucked and hung out with friends and sometimes found or founded new religions. These religions popped up constantly, some barely al-tered copies of one another. Most just glorified guided meditations; a few involved taking actual psy-chedelics, coupled with hypnotic, trip-enhancing visuals. And so the human animal became mostly an indoor creature, especially in San Francisco. A few people still went in to work inside high-rise offices, but it was increasingly rare.

The fist of the law still came down very occasionally, but when it did, it was mysterious and im-personal, just rumors. A silent disappearance in the night, a failure to return from an appointment with an accompanying automated text message to the next of kin. The legal system, and bureaucracy in gen-eral, had quickly given way to the algorithm.

Abram traced through this chain of events sometimes, watched it unfold like a movie behind his eyes. None of it mattered to him, none of it—except the change in the nature of time. Time had turned into one long nothing. Days seemed to pass like weeks, but then years would flash by like days. Abram made art as he had always done, but it meant nothing to him and was for no one. He went through the motions, brought in a bit of extra money sometimes. Edie did the same. They loved each other and their lives were simple and empty. Abram sometimes couldn’t tell if he was incredibly depressed or delirious-ly satisfied.

It was quiet outside the window, with just an occasional autonomous semi gliding past in the night. Abram sometimes felt like a gnat, a speck, suspended in golden amber, and time hung thick and heavy all around him. He brushed his teeth, set a mousetrap in the kitchen in the small space behind the stove, and went to bed.

4

Abram and Kenner sped out across a brass sunset, Kenner’s mirrored chrome truck flaring like a comet. They both settled comfortably into the amnesiac stupor of traveling through open desert. Raw possibility, everything waiting to be discovered and destroyed in the gargantuan, pitiless, anony-mous distance. Kenner had purchased the truck, cash, after inheriting a small amount from his grandpa and subsisted on money made chasing gigs, mostly hauling small items up and down the California coast. Now Abram hired Kenner and his truck, paying the gas money and all general expenses from his artist grant.

Abram made loose preparations to visit a series of abandoned and little-known airfields scattered like dusty, forgotten dioramas across the desert Southwest. He planned to photograph them, camp within them when possible, write down observations, and collect it all into a photo essay of some sort, or possibly a short novel.

They passed the town of Needles on Interstate 40 into Arizona, windows down to let in the cool, dry air of the approaching evening. Abram sat slumped in the passenger’s seat, texting Edie, lap cov-ered in assorted gas station snacks and crumbs.

“You hear about that virus outbreak up in Canada?” Kenner asked over the highway wind.

“Huh? Virus?” Abram said, looking up from his phone.

“Government is claiming it’s from melting permafrost, because of climate change, releasing path-ogens. I think it’s a cover story.”

“Why?”

“Because they’re totally testing shit on people up there. It’s obviously more population-control stuff.”

“What are you basing that on?”

“I’m basing that on the fact that governments do shit like that. They won’t stop until we’re all dead or infertile.”

“Sure, sure, they want us all dead. Or maybe it really is just thawing permafrost.”

“If they thought the thawing permafrost was actually dangerous, they’d just make it colder up there.”

“For the love of God, don’t start with your weather machine bullshit again.”

“Okay, okay . . . Didn’t I tell you, though, that the air would be so much cleaner out here? You don’t even need a mask. I love the desert. It’s like my natural environment,” Kenner said, smiling, drumming the steering wheel.

“Yeah, you’re a regular John the Baptist.”

“I think there might be another checkpoint up ahead. Or an accident. You see it?” Kenner said, squinting.

“Seriously?” Abram looked up again from his phone. “Where is your DMT-A? I don’t feel like hav-ing to answer a bunch of cop questions.”

“I majorly stashed that shit, man. They’d have to take the truck apart to find it. And anyway, the dogs can’t smell it. It doesn’t have a smell. It’s barely illegal anyway.”

“You better not get us arrested on this trip,” Abram said, struggling to open an organic protein bar with added nutrients for lung health. “It’s always amazing to me how habituated most people have be-come to being governed by surprise like this. I don’t really notice it so much until I leave the city. Ran-dom checkpoints, drones flying over, running our data. They always make it seem like we’re in the mid-dle of some complicated national emergency. I don’t know. I guess we are, though. Things just feel more static in the city.”

“No, man. It’s their strategy. It’s all about the gradual separation of the government from the people. Same thing the Nazis did in Germany. We didn’t have control before, but at least we had the illusion of control. Now people just let the government do what it says it needs to do. It’s like an invisi-ble monster that keeps everybody pacified by feeding them UBI and VR games.”

“Thank God for UBI.”

“I’ll tell you what these checkpoints are really about, though,” Kenner said in an inward reverie. “They’re searching for bioterrorists.”

“What?” Abram said, laughing.

“I’m for real. I have a friend, Jennifer, in Oakland. She’s part of a biohacker group. She does all that CRISPR-Cas9 stuff. She used to work at the Genomics Institute in Berkeley. She told me that the really wild shit is going on out here in the desert. Brain implants, germline engineering, hardcore genet-ic experimentation. She told me the government raided a bunch of labs out here recently. She said there are groups racing to create a human-pig hybrid. An embryo. Then implant it into a woman so she can give birth to it. There’s prize money involved.”

“Why would they even want to do that?”

“I don’t know. It’s like a contest, or like a joke, I guess.”

“That’s a hell of a joke. Intricate setup.”

“And the punchline is a pig-baby.”

“A chimera,” Abram added.

“A what?”

“A chimera. It’s a human-animal hybrid. Like in mythology. Think of the sphinx in Egypt: half human and half lion. Humans are hardwired to break up the natural world into categories to simplify things: flying animals, dangerous animals, bugs, trees, people. Anything that violates these categories, that mixes them up, provokes a strong primal response. Makes our world unpredictable. We tend to re-member category violations, and that’s why so many ancient stories incorporated them. Societies tend to channel their fears into the monsters they create. It makes their fears tangible. Rally everyone to-gether against a common enemy, the unnatural monster. Build religions around it. I did an art piece about it in a shop window on Valencia a few years ago. Remember that dog-head mask I made?”

“Kinda.”

“That’s a pretty expensive project, though, if it’s true,” Abram continued, watching the silent, blue desert move and then stop as they joined a small line of mostly autonomous cars waiting at the checkpoint. “Those hacker groups must be funded somehow.”

“Funded by who? PETA? Maybe people will stop eating pork after they hear a rational argument from a pig person in a suit?” Kenner said.

“I don’t know. Maybe a foreign government in the interest of sowing chaos in the United States. Or maybe they’re funded by a Christian death cult looking to bring about the end of the world by draw-ing forth a mythical pig-man beast?”

“Seems like they would’ve made a goat-man beast instead.”

“I guess you could use a human-pig chimera for organ transplants.”

“But if it’s part human, shouldn’t it have human rights? You can’t just harvest its organs.”

“That’s true. If it had a partially human brain, I guess it would have human rights.”

“Of course it would have a human brain. At least some percentage human,” Kenner said.

“People really need organs, though. At this point, a lot of people in California could use a new set of lungs. I think it’s an ethical bridge scientists will have to cross when they come to it.”

“Dude, they’ve come to it. They’re at the bridge.”

“Yeah, I don’t know. Maybe if we’re lucky, we’ll run into a human-pig chimera on this trip and we can figure out exactly where we both stand on the subject.”

“Maybe we will. Look out there at all that desert. It’s getting bigger every year. I feel like we’re sit-ting at the bottom of a dry ocean. There’s probably a chimera out there watching us right now. There’s gotta be.”

“You sure you aren’t too stoned to talk to this cop? Maybe we should switch seats.”

“That’s exactly what they would want us to do. If anything, you’re not stoned enough.”

“Okay, you’ve completely lost your mind. You better not get me arrested.”

“License and registration,” the cop said in a strange, abnormally lowered voice, shining a flash-light in the truck. “Are you a citizen of the United States of America?”

“Uh . . . Yeah?”

The cop stared at Kenner. He wore a tight black tank top with a heavy badge dangling obscenely near his nipple. His skin had the pallor of deli turkey. Sweat gathered into a drop on his cheek. Abram and Kenner watched the drop. The cop’s acrid body odor found its way into the vehicle.

A cop in the background dropped a clipboard. Another tripped and fell against a parked cruiser. They all sweat profusely. The cop waved the truck on without another word, as if suddenly snapping from a dream, remembering where he was.

“Is it just me or were those cops tweaked out of their minds?” Abram said, watching the check-point recede in the rearview mirror.

“See, I told you. There’s weird shit going on out here.”

“What do you think they were on?”

“I don’t know? Codephedrine, maybe. I heard all these middle-of-nowhere chickenshit cops dip into it. Stay awake for days, driving around looking for people to fuck with.”

“That was a dangerous situation. I hope to God we don’t hit another checkpoint. There’s got to be some way we can report those fucked-up cops back there.”

Kenner laughed. “Sure, call 911.”

***

They drove on in the dark, the road rising to meet them through the milky headlights. They turned over more outlandish theories as to the odd police behavior but arrived at nothing substantive. They revisited the chimera conversation and abandoned it. As surely as a train locking into a track, their conversation veered into wistful memories. Far from the light of any city or brutal lightbox truck stop, the stars shone like pinholes in a velvet blanket hanging low and loose above their heads. Two little boys in their fort. Long, comfortable pauses descended as the warm, hypnotic stupor of ceaseless desert driving set in. They checked and then rechecked their coordinates and went over the itinerary.

“Let’s try to see what’s on that memory card again when we get to the motel,” Kenner said, taking a long hit and tossing the emptied pipe into the middle console.

“Sure. I don’t know what we can do, though. The files looked corrupted.”

“I’ve got an idea about that.”

“Okay, whatever. Let’s pull off in a second, though. I’ve gotta take a piss.”

“You ever think we’re just a solar system orbiting a black hole? Circling the drain?” Kenner said, craning his neck to look up into the night.

“Uh, no, can’t say I have.”

“There are certain kinds of black holes that have a structure that would allow stars and planets to orbit for millions of years without getting sucked in. Maybe that’s why everything is so strange and fucked up. The basic laws of the universe are slowly getting ripped apart as we get closer to the event horizon.”

“Wouldn’t astronomers have detected a nearby black hole by now?”

“Not if it’s affecting us all mentally. Distorting our reality.”

“I guess. Seems like another one for your collection of untestable hypotheses.”

“It might be testable,” Kenner said. “I’m still working it out. It comes down to detecting causality violations. Anyway, look at how bright the Milky Way is out here, away from all the smoke and light pol-lution. That’s wild. I feel like we’re floating in space.”

“Yeah, keep your eyes on the road.”

“Up there, that white trail in the sky is a hundred billion stars, most of them with their own set of planets. You know eighty-four percent of the Milky Way is made up of dark matter? It’s invisible to us and we have no idea what it is. We only know about it because of how it affects the stuff we can see.”

“I’m sure you have a theory about that.”

“Sure, maybe the dark matter is love. Or some kind of primal god of chaos. Or both.”

“Let’s pull off here. I’m about to piss my pants.”

They took the next lonely off-ramp and were ejected into the parking lot of an automated diner kiosk gleaming like a green road flare. Not another structure visible to the blank horizon. Three cars in the small parking lot, two of them highway patrol.

“Just keep driving straight. I don’t want to fuck with any more cops tonight.”

They passed and went down the adjacent road and into relentless darkness. The road soon turned to dirt. They crunched to a slow stop on the loose gravel. Abram got out and blindly groped his way a short distance from the truck. Urinating into the cool night, his eyes adjusting, he could see a ramshack-le barbed-wire fence, and a few feet beyond that, he could just make out an odd silver-blue line neatly tracing the barely discernible horizon. He zipped up and squinted into the black, moving closer to the fence and carefully slipping between two rusty wires. The air felt thin and twisted around him, as if he were in the center of a mute vortex. He stood a few feet from the sharp, crumbling rim of a colossal me-teorite impact crater.

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams

The Fact of the Moon Is Stranger Than Most Dreams